SCOURGE written by Daniel McGrory for iWITNESS, 2004.

Numbers alone cannot hope to convey how AIDS has ravaged the southern half of Africa. The figures are truly frightening, with one in five adults across this region now living with HIV/AIDS.

Yet our obsession with statistics numbs our appreciation of the scale of human suffering, and the enormous courage of those touched by this scourge. Graphs cannot measure the remarkable efforts of health workers, or the strength of Africa's orphaned children, left to bring up younger brothers and sisters. In schools, villages and clinics across sub-Saharan Africa, tireless volunteers teach those infected with HIV/AIDS how to live with the virus and not die from it.

In hospices, dedicated staff make the final hours of those beyond help, as painless and dignified as possible. In millions of homes there are parents bravely determined to use what time they have left to ensure their children do not fall prey to this disease.

AIDS has cast a long shadow across this impoverished region. The epidemic has robbed communities of the vitally needed skills of teachers, engineers, and doctors, and put an intolerable strain on already poor economies.

The latest figures make disturbing reading. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that in the southern half of Africa in 2003 there were three million new infections, and 2.3 million AIDS deaths - 300,000 of them children. This region now has nearly 27 million people living with the virus, out of the 40 million infected worldwide.

Three million youngsters under 15 are now living with HIV/AIDS, according to the WHO, and every day sees 14,000 more people contract the virus.

What most concerns health workers is that these figures show how young women are the most likely to be infected, and they in turn can pass on the virus to their newborn babies.

The drugs that can prevent this happening are far too expensive for most communities to afford, so barely one per cent of expectant mothers have access to these medicines. In some countries the epidemic is still gathering momentum. In Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland 40% of adults are believed to have HIV/AIDS. This is unquestionably Africa's deadliest war, and right now it is losing the battle.

African nations are spending around $165 million a year to combat AIDS while the World Bank recommends a comprehensive plan costing $2.3 billion if the spread of the infection is to be arrested. To grasp what this pandemic is doing to community’s just pause outside cemeteries like Chunga in the Zambian capital, Lusaka, where 126 gravediggers hack away at the baked earth, and a permanent fog of dust swirls around the funeral processions that arrive every few minutes, with coffins strapped to car roof racks or carried on trucks.

People are so desperate and scared they are vulnerable to faith healers and bogus doctors who promise a cure when scientists admit they are still years away from that.

In this region there is no escape, you are either infected or affected by AIDS.Children grow up carrying the stigma of the disease, often burdened by the responsibility of being the only wage earner and having to provide food and shelter for surviving members of their family. In many villages an entire generation of 15 to 45-year-olds has disappeared, leaving only the very old

and the young to cope alone.

The man leading the United Nations fight against the disease, Dr Peter Piot, warns, "The most devastating social and economic impacts of AIDS are still to come". AIDS, he says, is the worst health calamity mankind has suffered since theMiddle Ages.

What gives some hope for the future is that the message of safe sex and other health programmes are beginning to work in many communities. Initiatives in countries like Uganda and Senegal have succeeded in cutting the rate of new infections by half, so the fight is not lost.

Danny, who worked around the world for the Daily Express and the Times and a close friend of Tom’s.

A Dinka mother and her starving children wait silently for food at the Medecins Sans Frontieres feeding centre in Ajiep, south Sudan at the epicenter of the 1998 famine that claimed an estimated 70,000 lives. Ajiep, Sudan 1998.

A scene at the feeding centre at Ajiep, southern Sudan, where thousands of starving people gathered during the 1998 famine.

Precious high protein biscuits are gripped tightly by a sleeping woman at Ajiep, southern Sudan in 1998.

Weakened by months without food, a desperately sick boy hangs onto a tent rope at the Ajiep feeding centre run by MSF during the 1998 Sudan famine.

Carrying his only possession, a food bowl, an emaciated boy approaches the Medecins Sans Frontieres feeding centre in Ajiep, southern Sudan in 1998.

Trying to keep warm a Dinka child wraps his arms around a thin body during the famine which struck Sudan in 1998.

Hunger claims another life as a Sudanese mother presses her baby into a shallow grave during the 1998 famine that struck Africa's largest country.

A well nourished Sudanese man steals maize from a starving child during a food distribution at Medecins Sans Frontieres feeding centre at Ajiep, southern Sudan, in 1998.

With silent dignity an elderly woman waits for aid to arrive at her stricken village near Anjar, Gujarat, after the earthquake of 2001.

A child plays with pigeons among the ruins of Bhachau, India, one of the worst hit towns after the earthquake of 2001 struck the region.

Workers clear away rubble in the town of Bhuj, Gujarat, in India after the earthquake of 2001.

Women carry water through the decimated city streets of Anjar, India, after the earthquake that struck the region in 2001.

A badly injured child is treated at a hospital in Anjar, India, after the earthquake of 2001.

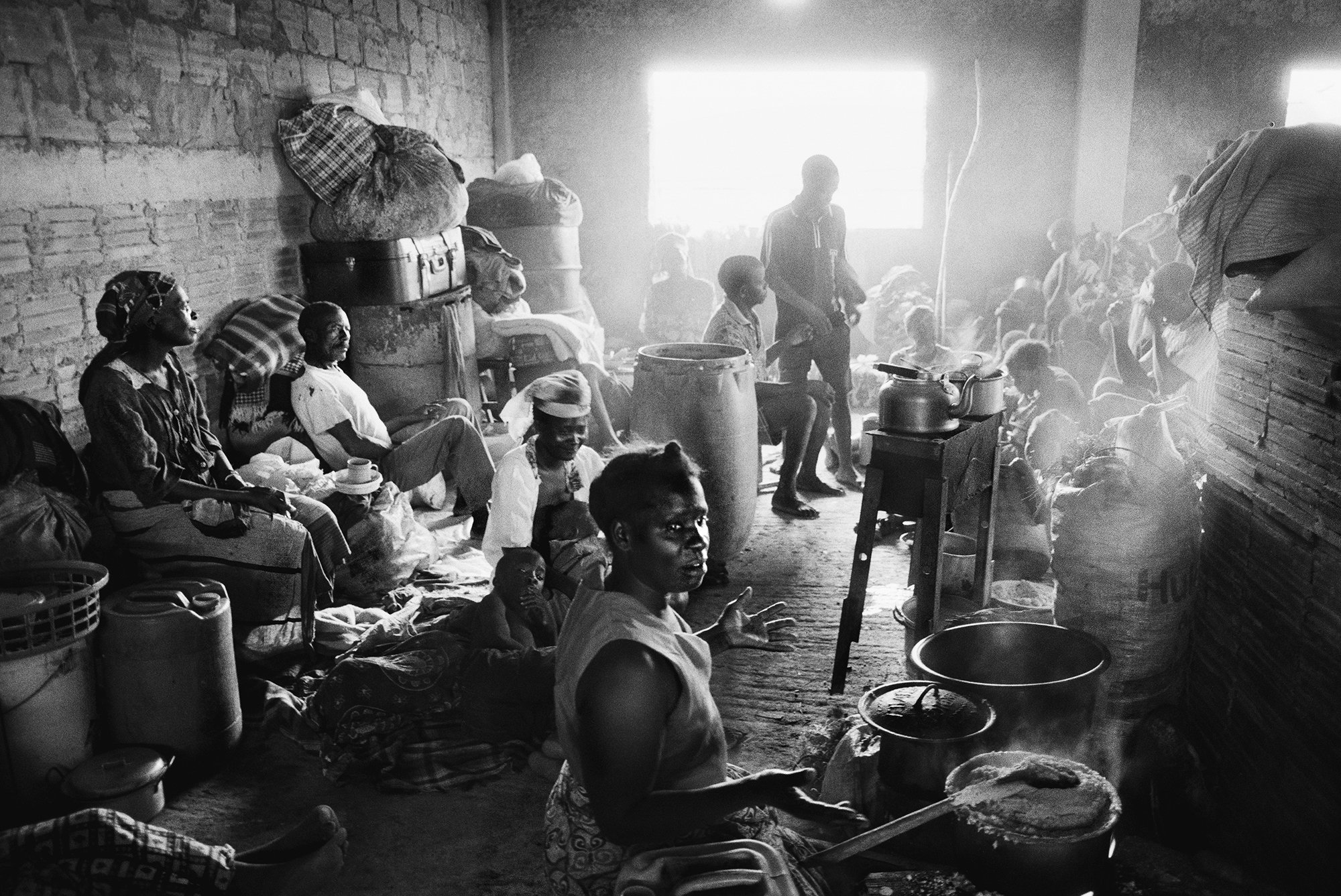

After escaping the rising waters people shelter from the rain in the upper floor of a half built house during 2000, when Mozambique was engulfed by floods.

Laden down with all of their remaining possessions, a family wades through the flooded streets of the Mozambique town of Chokwe in 2000.

Sheltering from a heavy mortar bombardment, 67-year-old Antonia Arapovic, hugs her neighbour's terrified child in the darkness of an underground cellar in Sarajevo 1992.

A woman holds a precious loaf of bread during the siege of Sarajevo which lasted from 1992 to 1996.

Nine months after the 911 disaster the 'Naked Cowboy' entertains crowds in Times Square, New York City 2002.

A girl lights candles in Union Square, New York, that became a shrine to those killed in the 911 attacks, 2001.

An outpouring of grief outside the family aid centre set up at the National Guard Armoury in New York City after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the World Trade Centre.

A young couple survey the flattened landscape where their house stood before the Indian Ocean tsunami struck Hambantota, Sri Lanka, on 26th December 2004.

Safiah Aji looks through the window of her destroyed home at Banda Aceh, Indonesia. She lost 50 members of her family when the Indian Ocean Tsumani struck the area in December 2004.

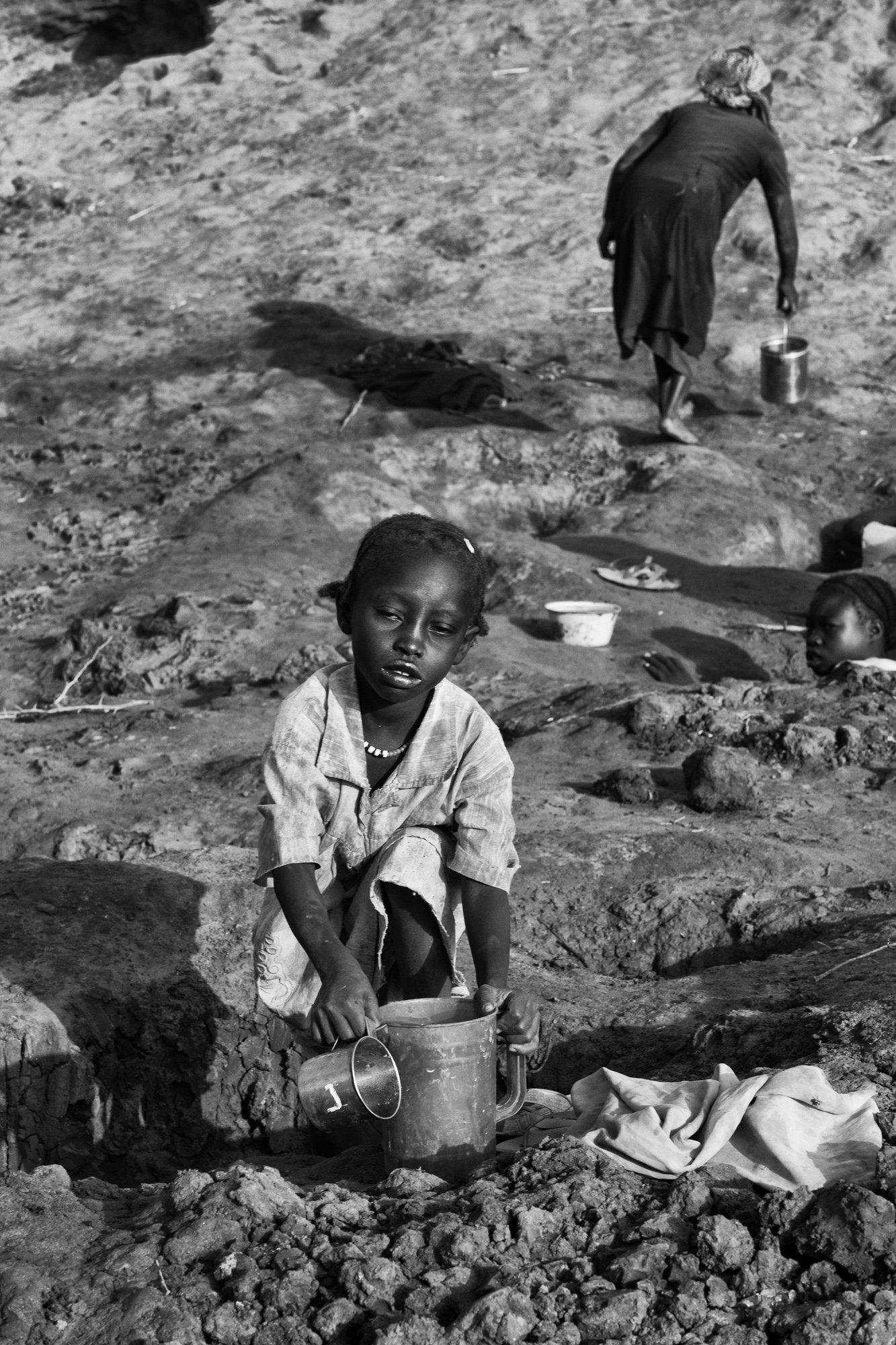

In March 2012 the Jamam refugee camp in Upper Nile State, South Sudan housed 36,500 vulnerable people who had fled across the border from their homes in Blue Nile State to escape the ongoing fighting between Khartoum’s government troops and the Sudanese Peoples Liberation Army. Water was desperately scarce in the camp and as people formed long lines at taps in 40 degrees of heat, frustration and fights broke out.

Nearby at a dried up watering hole, every day dozens of thirsty children dug deep holes and caves into the parched earth to scoop up cups of muddy water. 16-years-old Sarah Yabura said “Getting water from the holes is very difficult and dangerous. I’m afraid of the snakes. Life here is difficult and it will get much worse during the rainy season because this area will be flooded. Our whole family is here except my grandmother who stayed in Blue Nile. I have no hope for the future because there is no school here, no good life and my future is dark." 2012.

People are weakened by vomiting and diarrhoea but NGO’s believe the real danger will come when the rains arrive in a few weeks time. Marcel Pelletier, a water engineer with the ICRC says, "In my ten years' experience as a water engineer in conflict-affected areas, I would say the water shortage in Jamam is as severe as anything I've seen. It is a desperate situation.” 2012.

Marcel continues, “People are digging by hand into the ground on the site of dried-up watering holes and scooping up any water they find. These people are thirsty and are spending six hours outside with jerry cans in the intense heat.The rains will come in about 5 weeks. Far from being the solution, the rains will actually make things worse. We have a real humanitarian crisis on our hands.” 2012.